Reuters published a story yesterday that seems alarming on its face — Chinese manufacturers may be putting secret communication devices in our solar inverters. 😱

Quoting the piece by Sarah Mcfarlane, about the potential of secret communication equipment inside solar inverters:

U.S. energy officials are reassessing the risk posed by Chinese-made devices that play a critical role in renewable energy infrastructure after unexplained communication equipment was found inside some of them, two people familiar with the matter said.

Then, later in the piece, alleging similar things about some batteries:

Over the past nine months, undocumented communication devices, including cellular radios, have also been found in some batteries from multiple Chinese suppliers, one of them said.

And what’s our source for this? Well, two people familiar with the matter. Unnamed folks who have some amount of communication with US energy officials. Officials who clearly have our best interest in mind, considering that the current US Secretary of Energy is Chris Wright, who served as CEO of various fracking companies over the last 30 years, and is on the record as being an enemy of the clean energy movement.

This does not eliminate the possibility of the technical details being correct, to be clear. I’ll get into that in a moment. But we must be skeptical of the source of this information, given that the US government is not terribly interested in being truthful with its populous right now.

Also, keep in mind that no brands or models of equipment have been named. Makes it hard to follow up on this claim, which may be intentional.

On the technical side, this reminds me of a very famous story in 2018 from Bloomberg called “The Big Hack”, which was widely seen as debunked, despite Bloomberg doubling down on the story in 2021. The premise was that China was using Super Micro to compromise the data centers of US tech companies with secret hardware that nobody knew about, a claim that remains unsubstantiated.

Now look, “unexplained communication equipment” sounds scary. But there’s something extremely important to know about unexplained communication equipment. That stuff must actually connect.

Let’s take the cellular radios, for example. Cellular radios must have an actual connection to the local cellular network — you need to have a deal with a company that has access to those actual cellular radios, make sure those SIM cards or eSIM registrations are in each inverter, and have them active from the very beginning of installation. Hypothetically, you could set each inverter to turn on the cell signal two months after first powering on, but this would all still be very easy to confirm. Spectrum analyzers are like $200 on Amazon.

Same with satellite connections. Theoretically, there could be Chinese satellites over the US that would eliminate the need to make deals with US cell companies or towers, but you’d still need a persistent connection in order to get anything done, something that should be extremely easy to substantiate.

Anything else would be laughably complicated and stupid, barring some new technology that only China knows about.

As an aside, hardware CAN sometimes have things in it that simply aren’t used and will never be used by the software. When I hear someone talk about something unexpected in a chipset, I always think back to the iPod Touch 2nd Gen, which had FM radios built-in, despite never enabling the functionality. Sometimes it’s easier/cheaper to buy a hardware package with more connectivity than you need, and only support part of it.

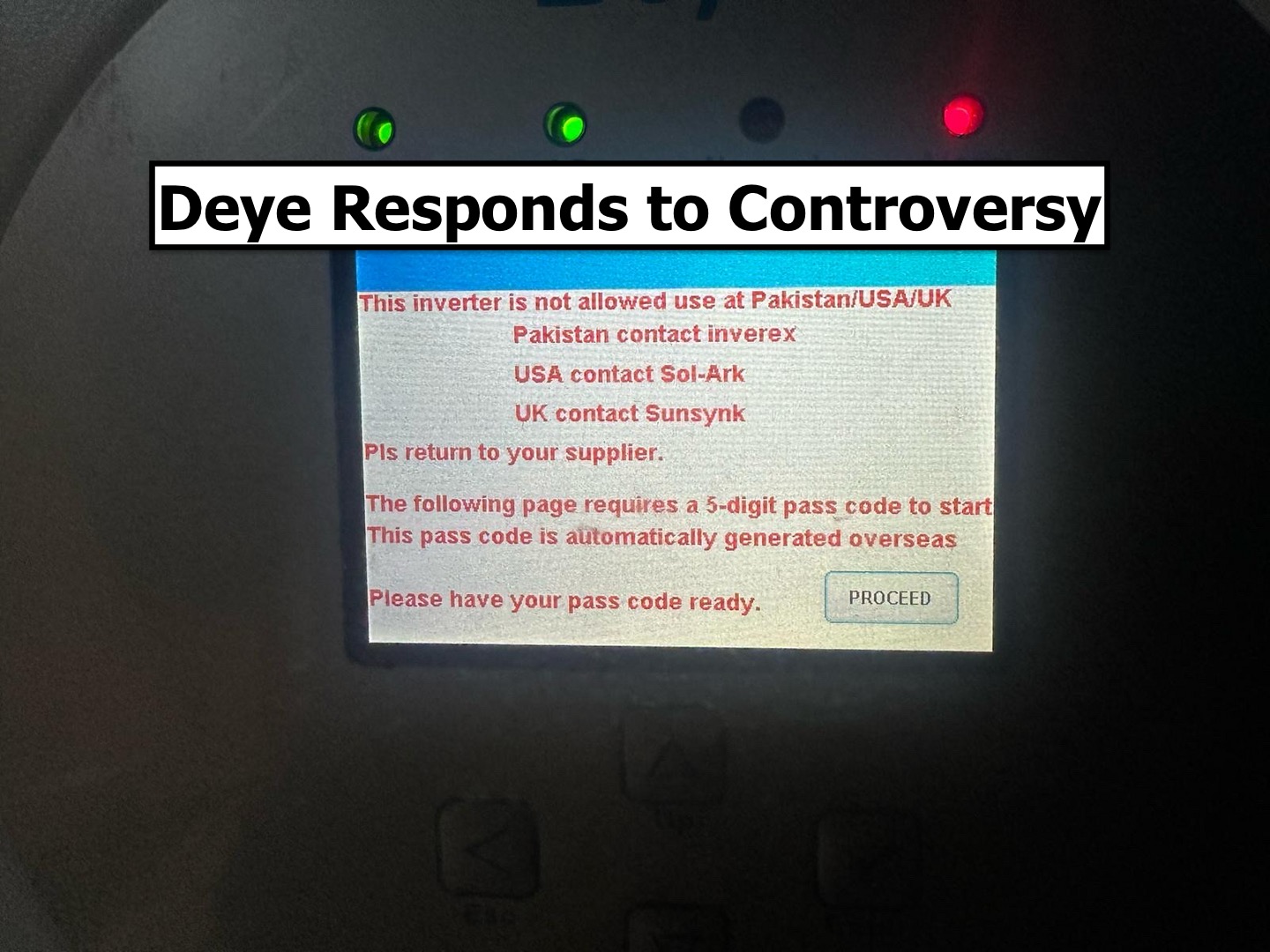

The biggest threat to solar inverter security is the software that uses the advertised communication hardware. As demonstrated by Deye when I wrote about them in November, any company that has its product monitored by its own systems usually has the ability to shut it down. This is a well-known concern about internet-of-things devices, and while Reuters’ piece names only utility companies as being at risk for this, utility companies are usually the only ones well-equipped to battle something like this.

Hardware is a silly attack vector for communication, and only sounds scary. If there is an actual danger, we need substantiation, and this kind of supply-chain hardware sabotage has simply not been proven by anyone to be real.